At the beginning of this year, my wife’s cousin F died suddenly in his sleep. That sentence doesn’t begin to convey the weight of losing someone so young and seemingly in good health, and so I’ll mention how hundreds of his friends came to his funeral—so many that one of the police officers there to escort us remarked that he’d never seen such a crowd in all his years escorting such processions. “He must’ve been a cool guy,” the officer said. To press his point, I could describe F’s prowess at the pool table or marvel about his savant-like recall of books, music, movies, and culture in general. I could mention that he was so beloved at several drinking establishments in the Mission district here in San Francisco, that the owners permanently reserved places for him at their bars, and regulars referred to him as the mayor. Because F was so deeply familiar with so many things, he had an easygoing way with people, an ability to make anyone laugh and feel heard.

After he died, F’s family (i.e my in-laws), being passionately devout Filipino Catholics, held a prayer vigil for him, followed the next day by a funeral mass. Then for nine more days, the family gathered to pray at his parents’ house where he had still lived—reciting countless Hail Marys, the five sorrowful mysteries, have mercy on the soul of F… over and over. This tradition of praying for nine days is called a novena, which a friend of mine aptly described as “next level Catholicism.”

Some folks opted out of the prayers and mingled instead in the kitchen or outside on the front porch. I was one of these, as F himself was during past family prayer gatherings. He always made us heathen folk laugh with his brand of dry commentary, as he surveyed the scene in his man-of-mystery way. During the novena at his house, I felt his absence. I felt his presence too. Since F wasn’t the praying type, I couldn’t help wondering what he would have said about the prayers offered on his behalf, especially the pleas to save his soul. Something wise and funny, no doubt.

Prayers and other kinds of recitations can become so familiar through repetition that you stop paying attention to the actual words, but I didn’t grow up with these particular prayers, so I am still struck by them. Have mercy on the soul of F... I wondered whether anyone in the room really worried that F’s soul was in peril, that God might punish him for eternity unless they asked him not to. I doubted it, and I understood that the act of praying was the essential thing, not the words spoken. It was a familiar way for loved ones to gather in grief and honor a lost son, brother, cousin.

My wife’s family is a big one, and we have gathered for many deaths in the time that I have been a part of it. Too many. I used to participate in the family prayers, but I stopped some years ago for the same reasons I stopped going to church. As a kid I became aware of a disconnect between the words I was speaking and what I actually believed, and it never sat right with me. I didn’t like performing belief, or certainty about things that seemed unknowable, starting with the question of whether the divine being I was addressing existed in the form we imagined (solitary, all-powerful, humanoid, male), or at all. I felt like I was being dishonest, and because it was sacred terrain, it seemed wrong to fake it.

Looking back, I think this was probably the itch that began my journey out of the church, and it’s something I have failed to touch on in previous attempts to write about this. In other tellings, I have framed this story as a turning away, my rejection of an institution that I came to see as hypocritical and misguided, particularly with respect to LGBTQ people. That’s not inaccurate, but it’s incomplete. The truth is I started to leave the church some years before I had any of those kinds of ideas.

It might have begun with the fact that church is boring, and I only ever went begrudgingly. Does anyone under the age of 70 actually enjoy the church part of church? (Maybe it’s important to note that I’ve never attended one of those megachurches with live rock bands and theater lighting, nor a Pentecostal church with delirious glossolalia and faith healing and maybe snakes, nor a gospel church with a boisterous choir and spontaneous amens from the congregation. Those don’t seem boring at all).

My parents obviously felt church was important, and I wanted to understand why (or come up with convincing reasons why not). I got that it was supposedly good for us, like boiled zucchini or sleep or other things I resisted, but I couldn’t see how listening to old bible stories (some of them deeply weird) followed by common sense lectures week after week was a good use of anybody’s time. Some ministers could rip a good yarn, but most could not, and I remember feeling like we got reruns a lot of the time, and a lot of sermons that were perfunctory wrappers for basic life lessons: Be kind to other people. Don’t be selfish. Don’t get too attached to things that don’t matter. It’s good stuff to hear, but dozens of times? Plus, it was obvious even then that some of the long-time regulars hadn’t absorbed those lessons, so a habit of church attendance didn’t seem to correlate with actual human decency.

The “higher” moral and intellectual rationalizations for church never made any sense to me, but for a while I was happy enough to go for more mundane reasons. As a kid and through my teens, I mostly experienced church in the Bryn Athyn Cathedral, a distractingly beautiful venue whose grandeur I came to appreciate more fully in retrospect. Here it is:

During services, I enjoyed how the sunlight glistened through the majestic stained-glass windows, and how the music resounded in the space as we sang along with the organ. Most of all though, I was happy to see my friends there every Sunday after the service ended. My parents clearly enjoyed the social aspect of Sundays as well, and while they chatted with other grownups about probably mortgage rates and strategies for avoiding traffic around the Philadelphia metro area, we kids ran around on that soft green lawn.

That was good enough for a while, but once I became old enough to make the choice for myself, I stopped going to church—outside of occasional weddings and funerals—and I stayed out of churches until I met my current wife and her Catholic family. I used to go to church with her because it earned me points with her family, and also because Catholic mass was something new for me. I was genuinely curious and interested, and there were things I appreciated about it right away, things I still appreciate. I like the communal spirit of the Rite of Peace, where members of the congregation exchange nods or handshakes and say, “peace be with you.” I appreciate the Prayer of the Faithful for the way it directs compassion towards current real-world suffering. And I enjoy the unintended comedy when the priest proclaims “mass has ended,” and everyone responds, “thanks be to God!”

Now I’m back to avoiding church for the most part, though I dutifully attend at Christmas and Easter, and begrudgingly a few other times a year, usually for school-related reasons. I still have the same complaints—that it’s boring. Usually it’s just run-of-the-mill boring, but once in a while it’s so excessively and unnecessarily boring that I can get a little angry when I think about it.

Beyond simple boredom, I also feel conflicted about church. That feeling wasn’t something I had to contend with growing up in a branch of Christianity that is decidedly marginal and obscure, but it entered the picture when I was introduced to the Catholic church. I’m talking in part, of course, about all the sexual abuse scandals, involving not just crimes perpetrated by individual priests, but shameful denials, coverups, and deflections on an institutional scale. And then going back further into the church’s history, it gets much worse. The crusades. Slavery. Colonizers destroying indigenous communities and families in the name of god. Truly horrifying stuff that we have barely begun to reckon with, some of which was carried out as sanctioned church policy and vigorously rationalized using scripture. Of course the Catholic church is not alone among churches in its culpability for sins of colonization, slavery, and sexual abuse. I single it out because it’s the only church I feel any obligation towards these days. It’s hard to know what to do with all that. It’s not fair to condemn one little parish for the sins of the Catholic church writ large, but sitting in the pew still feels like an exculpation that I don’t want to offer.

My kids don’t like going to church either (again, who does?), but because their parents are divided on questions of faith, unlike mine, they share their feelings about it more openly than I did, and they are probably more hopeful about the possibility of an out. While on a road trip not too long ago, my daughter straight up asked me why I am not religious like her mom. I thought about it for a minute and then I told her that I think of religious belief as a spectrum, not a binary yes or no thing. I explained to her that I do believe in various things to different degrees, and that her mom does too. Then, thinking specifically of Catholicism and of her mom (but without mentioning either directly), I said that even different people who belong to the same church believe different things, that this is true even in a church that is very clear and specific about what you’re supposed to believe. Even then, I said, members of the same church embrace some of what the church commands and just go through the motions with other things, because a person can’t intentionally decide what to believe. Belief is a deeper, unconscious thing that develops in you.

Some years ago I read that a number of evangelical pastors are closet atheists, and it doesn’t surprise me at all. It’s hard to break away from a church, and also a church can afford important things that don’t require belief, which I’ve touched on here. A community organized around belief is a powerful thing, and maybe one that’s impossible to replicate in the secular world. There’s a certain kind of automatic belonging that I remember from the church lawn of my childhood, and that I can feel at auntie’s house during prayers. Also, churches codify morals and values for people, relieving individuals of the effort that takes. Finally, churches assure us that life doesn’t end when the body dies, and that our dead loved ones are still around somewhere, so that we can talk to them, and they can hear us.

I refer to myself as an atheist, by which I mean an absence of belief in god, etc rather than a belief in their absence, but I haven’t shed my sense of the sacred. Sometimes my kids ask me to elaborate on what I do believe, especially about god or about the afterlife. I tell them I believe in mystery, that I am comfortable with the mystery of it all. When they ask me to be more specific, I like to point out that even the natural world is full of mysteries. Forget what I think about the supernatural or spiritual, I will say, because I don’t even know how to draw a line between natural and supernatural.

A few hundred years ago, humans knew nothing about light or sound frequencies that lie beyond our human senses, or lots of other things we now claim about reality. Take quantum particles for example, and how their behavior seems to depend on the presence of human consciousness, or at least on whether they are being observed. These are things that science barely understands today, stuff that would have been considered supernatural or even downright crazy in ancient times. And when we talk about nonvisible light or inaudible sound frequencies, we should add an asterisk and add “to humans,” because bees and birds and jellyfish experience very different worlds than ours, even though it’s the same world! We don’t know what it’s like to live as a jellyfish, so I hesitate to make any claims about how our consciousness might experience life after this meat suit expires.

Life comes at us fast sometimes, however, and this question of life after death has interjected itself a lot this year. First there was F, whose loss was so jarring that I still feel it in my body as I type this. And then my wife’s mother died early in the summer. Her passing was very different, because she had been completely incapacitated and requiring round-the-clock care for the past five years as a result of a massive stroke. Her death released her from that liminal, trapped existence, so there was a degree of mercy to it. Also, she was a woman of deep faith, so there was no incongruity or dissonance in the prayers that went along with her passing. Prayers were her love language, as one of the cousins put it, and the family honored her accordingly. Then, following the death of my mother-in-law, several of our good friends also lost parents in close succession. We have arrived at that time in our lives, we all acknowledged gravely at each gathering.

There is comfort of course in the idea that they live on somewhere basically as they were, but once again it was my curious daughter who asked good questions as she considered these kinds of assurances from aunties and cousins about her nana: When we die and go to heaven, she asked, do we stay the same age as when we died? Because it doesn’t make sense to still be old, but it also doesn’t make sense to start over as babies.

The more I ponder specifics like that, the less I am able to reconcile terrestrial concepts of time and physical existence with any version of the afterlife offered by a church. Nonetheless, I lean towards believing in some kind of eternal existence in part because of experiences I have had in meditation and with psychedelics where I felt like I entered a state of pure consciousness, absent all thought or feelings (impossible to really describe), and other times where I felt the boundaries of my self dissolve into a vastness without time, which I perceived to be true reality, and where this world was revealed to be a kind of veil or illusion. There’s no way to write about those experiences without it sounding trite or woowoo, but they were profound and very real. And since many other people have had similar experiences—likewise through meditation or psychedelics, but also as a result of near death, strokes, and other doorways—I believe it is an indication of… something.

To be clear, I don’t interpret these subjective experiences as glimpses of the actual spiritual realm that awaits us. Without invoking the words “spirit” or “realm” at all, what I do take away is an unshakeable sense that consciousness is not an emergent phenomenon of our physical bodies. It’s not coming from our brains. Virtually everything else might be an illusion, but I feel my existence as a fact, one that becomes clearer when everything else falls away. I simply am, and you are too, and we will continue to be when our bodies are gone. Where and in what form is part of the great mystery. I and you and everything might all be just one thing.

It’s just a sense though, not a claim, and none of it necessarily requires a supernatural dimension, by the way. Humans were unaware of quantum reality a century ago, and there’s almost certainly a vastness we are blind to today. As the writer Elizabeth Gilbert put it recently in an interview, “we are five Einsteins away from even knowing what questions to ask.” I feel no need to insert god into those gaps, nor do I feel a need to pretend the gaps don’t exist, as some secular folks do. When asked what happens after we die, for example, too many people respond glibly. We just become worm food, they might say, subscribing to a brand of certainty that is just as fallacious as the religious kind yet offers no comfort at all.

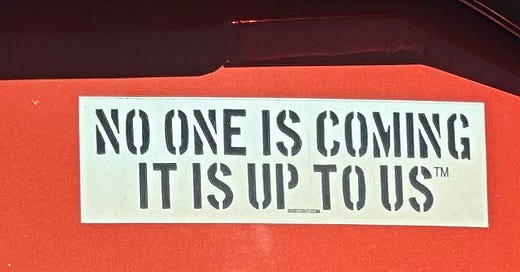

I stopped going to church because I stopped buying in to the purpose of church, but hidden in there is the assumption that purpose matters. It may be a lingering effect of my religious upbringing to imagine that we are here for a reason, but purpose doesn’t require religion or god. It does not necessarily imply that some greater force actively planted my consciousness into this incarnation. It could instead just be a statement of intent: I exist here and now, and therefore I want to make something of the opportunity.

As for what that translates to, at minimum I think I owe it to myself to be fully present for this incarnation (which is easier said than done by the way). Beyond that, I come back to the idea that gathering together as humans is itself valuable and gratifying. At auntie’s house after F died, it didn’t matter so much if we prayed, or if those who prayed sincerely believed the words they were speaking. It mattered that we were there together.

Our mutual existence—on this earth, at this time, in these bodies—is a great gathering. We can simply be here for each other.

A thoughtful, poignant essay. It’s interesting that it came the day after I’d had much the same conversation with a son of mine. A son whose ideas I respect and many of whose conclusions I share. I think there’s a reason your blog and our conversation were congruent. I think there’s a reason most things happen. I am old. My belief has become strong and more and more simple as I live. Our job is to be kind to others and help them in any way we can.

Oh, and tell your little girl who was named for me, that I believe when old people go to heaven they awaken as themselves and grow younger until they are simply adults - really nice ones.

I recommend the book Parenting Beyond Belief and the UUA.org's religious education curricula. It's about exploring one's own values, learning about the different faiths of the world and what parts might resonate with each individual, and respect for others. I feel that inculcating one's child with one's own values provides a much better inoculation against, say, cults because the child is well-grounded and less likely to be swayed. The child can say "does that align with my values?" and judge accordingly. Unitarian Univeralists' values are secular humanist, "good without god" values that align with what Lakoff would call "progressive values": nurturing compassion, empathy, and working together to reach a common goal.

I remember one summer I volunteered to do a children's class and, as a linguist, I chose language origin myths. Re-reading the Tower of Babel story I was shocked at just how antithetical it was to the secular humanist values I had taught my children. Here you have a group of humans who have worked together using creative engineering to build something impressive, and along comes a petty, narcissistic "father" god who want humans to be never grow up and be independent, so, petulantly, he ruins their tower and curses them to all speak different languages. "Hey kids, what do you think of this god? Would you worship him?" Clearly the answer would be No. Neither, we decided, would he be a good role model. As an adult, I find the Bible to be Rated R, inappropriate for children, and every time I try to read something in it, I am shocked and appalled. As a child, I found it far too inconsistent and illogical to figure out--particularly with Swedenborgians constantly saying "but that actually means this!" Huh?!

(One favorite memory: Minister--"'Man' isn't sexist, it refers to all human beings." Me--"Then the 'man and wife' in the marriage vows means you allow lesbian marriage but discriminate against gay men?" Minister--no answer. I never understood their "logic.")

When my kids were in upper elementary we read all the Rick Riordan books. We didn't talk about whether or not gods existed, but rather, "why do humans need gods? Is it for a sense of safety--would you feel better with a supernatural being watching out for you?" My son, who hadn't even wanted the tooth fairy to come near his pillow, was not keen on supernatural beings. I asked "if you were going to choose I god, which one would you choose and why?" I would choose Athena, I said, as she is the patron goddess of my alma mater, and as the goddess of war strategy AND of domestic life, a good example of, imo, fierce motherhood. My daughter chose Anubis--she liked the dog head and she's into liminal spaces. Focusing on gods as a "need" rather than "do they exist" is a nice bit of verbal aikido to disengage from Christian apologists.

As young adults, my son is firmly atheist while my daughter is interested in religions to the point of considering minoring in religion. She tells me "they're not all like Christianity!" Both my children, I am proud to say, are collectivist, compassionate, empathetic, intellectual, and supportive of justice. They, too, thought church was boring. I often went to the UU Church alone to learn what to teach them. As Lakoff says in Don't Think of an Elephant, it's all about values and framing them in a way that works.