It feels like a weird and perhaps frightening time to be an artist, or to have artistic aspirations. Not long ago, it was common to imagine that the next wave of jobs to be made obsolete by machines might be so-called menial and repetitive ones like fast food work. Intuitively this seemed like a natural next step, an evolution of what happened with manufacturing.

So a lot of office workers were feeling pretty complacent about their job security or at least blissfully unaware of AI in that sense, but then Chat GPT exploded onto the scene and made it clear that its immediate targets are various kinds of knowledge work and creative fields, a fact that shocked and surprised a lot of folks who hadn’t helped develop AI either directly or proximally. Now anyone who has settled into a career coding web or mobile apps or writing marketing copy, or press releases, or scripts for a documentary series or children’s tv, is feeling anything but settled about their professional future. Generative AI can already do “creative” work of this caliber much more efficiently than humans, and we’re just at the beginning of this revolution. People working in these jobs are already using AI to produce their deliverables, and increasingly it must feel like they are helping to train their replacements. There’s never been a better time to consider a future in HVAC repair or nursing.

Efficiency is a sacred tenet of tech, maybe the most sacred tenet of all. Arguably it’s the whole point of tech, and many industry leaders have said as much. The E in DOGE does not stand for effectiveness or efficacy or expertise. It stands for efficiency, and the most vocal of the tech overlords—Musk, Andreessen, Sacks, Ellison, Thiel, et al—are obsessed with a particular brand of efficiency that they extol on their podcasts and in their tracts, manifestos and excretes.1 It’s clear from their own words that they dream of the day when AI can either replace all the workers or reduce the bargaining leverage of their employees to such degree that they meekly submit to the will of the bosses.

It is their doggedness and fervor to engineer this new age of their dreams, where human creators are marginal if not obsolete, that led to the 2023 writers guild strike and a concurrent backlash from thousands of authors objecting to LLMs using their work without permission. So yeah, tough time to be an artist.

All of this has fueled a lively discourse about the definition of art and the value of art in an age of generative AI. In practical terms it’s becoming harder and harder to tell whether something was made by a human, which either means that AI is able to (or will soon) produce art, or art is something else, something more than what’s being produced. Artists are at pains to explain how art is indeed something more than the final output, and in some ways their attempts at this remind me of conversations I had with my roommates back in college, who were engineering majors and baffled by the idea of art as a real vocation as opposed to a cute hobby where you make stuff on the side.

To make these questions more concrete, consider Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (Netflix) from a couple years ago. Here’s the trailer:

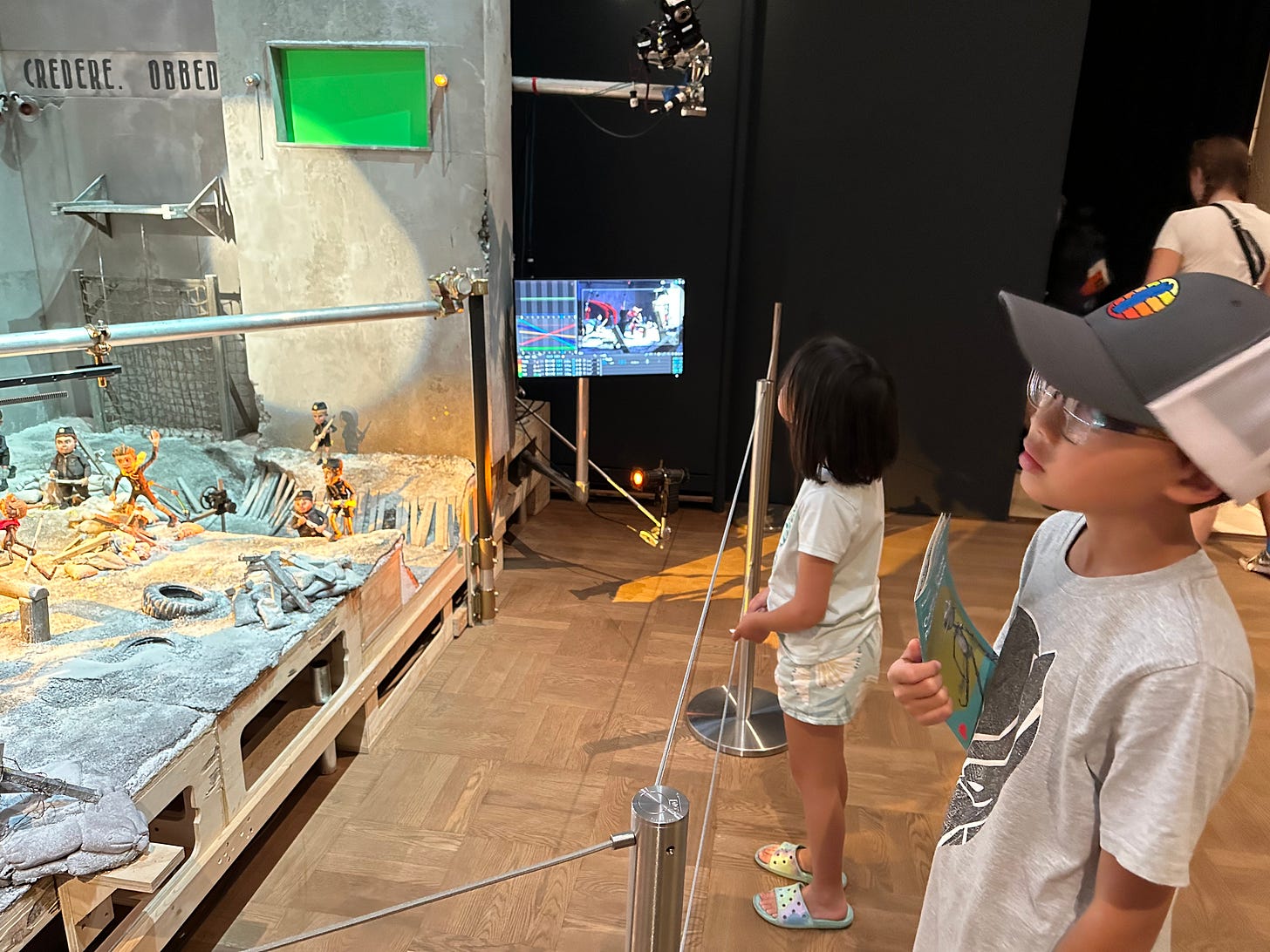

We watched it with our kids when it came out around Christmas 2022 and really enjoyed it. Fast forward eight months to when we were in Portland OR visiting family, and we stopped by the Portland Art Museum, which featured an exhibit about the making of the film. Until that day, I had no idea it was done in stop motion (by legend animator Mark Gustafson). I had just assumed it was computer animation.

Here’s a collection of some of the Pinocchio faces they made for the production, which they would swap out frame by frame to make him talk:

Let that sink in. A human person or people would remove Pinocchio’s face and replace it with another one twenty-four times in order to produce just one second of him saying words. They did that for every character, some of which were more complicated than Pinocchio, with separately-replaceable eyes and mouths:

Here’s a time-lapse that gives a sense of the work involved as well as the scale of the figures and sets:

Here’s another time-lapse just because it’s so freaking cool:

Here’s a figure for one of the characters, half-dissected to show its moveable skeleton:

The exhibit even included one of the crew’s workbenches:

Now consider the fact that when I first watched the movie, all of this was lost on me. To the extent that I thought about it at all, I assumed it was computer animation. Does that mean all of the time and money and effort that went into stop motion was wasted? For the sake of argument, let’s say it was possible for a computer to produce exactly the same result. Does it mean anything to know now that it was made so painstakingly by people?

I can’t help thinking that my old engineering major roommates would laugh at the question and that the efficiency-worshiping overlords of tech might be a little incensed. Of course it’s a waste, they would say. That thought makes me sad, but in a way it also makes me retrospectively both grateful and surprised that Netflix—a tech company—was able to see it differently.2

When we watched the movie again, we experienced it differently. We were aware of multiple layers.

The science fiction writer Ted Chiang had a piece in the New Yorker a while back that tackled some of these questions about AI and art, and he addressed the value of human effort this way: “any writing that deserves your attention as a reader is the result of effort expended by the person who wrote it.”

He argued in fact that the quality of the final product might be less important than what goes into creating it. Commenting on the public backlash to a certain Google commercial, he says:

The significance of a child’s fan letter—both to the child who writes it and to the athlete who receives it—comes from its being heartfelt rather than from its being eloquent.

And more generally…

What makes the words “I’m happy to see you” a linguistic utterance is not that the sequence of text tokens that it is made up of are well formed; what makes it a linguistic utterance is the intention to communicate something… [and] When someone says “I’m sorry” to you, it doesn’t matter that other people have said sorry in the past; it doesn’t matter that “I’m sorry” is a string of text that is statistically unremarkable. If someone is being sincere, their apology is valuable and meaningful, even though apologies have previously been uttered. Likewise, when you tell someone that you’re happy to see them, you are saying something meaningful, even if it lacks novelty.

Art has intentionality. It can be driven, for example, by curiosity, a question to explore. It can come from a desire to provoke people or to celebrate something. Art can also be about the journey along the way to the final output, including the stops and hiccups and side roads. The blood and sweat are often part of what makes a thing into art.

Mistakes and imperfections can be essential elements too. The Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi refers to an aesthetic that embraces imperfections and incompleteness. Similarly, kintsugi (“to join with gold”) is a Japanese technique of filling cracks and breaks with gold to both restore wholeness and celebrate flaws. AI makes mistakes sometimes, but it would take a human heart and mind to incorporate its mistakes into a work such that they reflect an artistic choice.

AI can’t be curious, and it can’t desire. AI doesn’t have intentions, so in that sense it doesn’t really make choices or have a process.

Efficiency is important part of an artwork, in the final product that is. When I compare a great television show to one that’s merely good, one of the key differentiators is efficiency, the sense that there’s not a single wasted line or camera shot or even prop. This applies to literature (no wasted words) and painting (strokes), and every other art form, but an it’s an interesting paradox that the path to the final product is often anything but efficient.

As a final note, it’s true that so much of manufacturing is automated today. But a lot of manufacturing still involves a surprising amount manual labor, even craftsmanship. Baseballs for example:

When I hold a baseball now, or pitch one to my son, it feels different knowing this. I like knowing this about baseballs. That’s a digression I guess, which is a form of inefficiency. Is it a wasted stroke, or does it make structural sense?

What do we call “tweets” now that Twitter is changed to X? My long time friend and podcasting partner at Satellite Haiku, Milo, proposes to call them “Xcretes” or “excretes,” which is perfect.

I didn’t know where to fit this in, but it occurred to me that some kind of “generate an article for me” or “rewrite with AI” feature would not feel out of place on Substack, since this is popping up everywhere. I’m happy that Substack has eschewed this so far, and I hope they keep it that way. #TeamHuman

Shawn- I fully appreciate your pointing out how art is somehow often more than the end goal. Animations, and more, I’d agree tactile work is a way of seeing, and in a strange way, molding the person taking on the act of art. BTW, Love the Explora rocket-launch pic! 🙌🏼

What a thoughtful, surprising essay. Surprising in that I too had no idea how much human work went into a particular art form unfamiliar to most of us.

"In Praise of Slow Art" struck me personally. I'm a writer and once a novel or a non-fiction work is published and out there, it lingers for a while and after the initial comments, pretty much sinks into oblivion. Occasionally though, you hear from a reader as I did three days ago, telling me how much a long ago piece meant to him. This kind of affirmation forms an instant connection between reader and writer, heart warming and precious. Not something AI can enjoy.