Robot Plumbers and the Limits of Extrapolation

AI researcher Daniel Kokotajlo, who made news last year when he resigned from his role at OpenAI, recently put out a report called AI 2027 that predicts alarming impacts of Artificial Intelligence to happen alarmingly soon. It’s the product of a collaboration among a small group of AI experts calling themselves the AI Futures Project, presented as a compelling choose-your-own-adventure sci-fi scenario. I won’t summarize it in a general way here, but I think people should read it, or at least go and listen to Kokotajlo discuss it on any one of a number of podcasts. I listened to him on Making Sense with Sam Harris and Interesting Times with Ross Douthat.

Around the same time that AI 2027 came out, two other computer scientists—Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor—published a counter-perspective in a white paper called AI as Normal Technology. It’s a dryer, more academic read than what’s presented in AI 2027, and it draws more transparently from other disciplines—history, sociology, economics, etc—for its conclusions. As with Kokotajlo and the AI Futures team, you can find Narayanan discussing his take on numerous podcasts. I recommend listening to at least one of them if you can’t carve out time to read the actual white paper. Finally, The New Yorker published a good piece on the dueling perspectives, which is a good read as well.

The two perspectives highlight how this territory represents both a technology problem and a people problem. Kokotajlo paints a vivid and credible picture of the human forces that are driving things forward, possibly towards an abyss. He has first-hand experience of Silicon Valley ambition and arrogance combined with its unique kind of naivety. He also points to the arms race dynamic between China and the US with respect to tech in particular, and it’s hard not to accept his argument that this will fuel the rationale for further removing obstacles to AI. The devil is in the details however, and Narayanan for his part drills deeper than Kokotajlo into what some of the actual obstacles might be, especially with respect to things like computing power and sociocultural friction.

A couple of Kokotajlo’s predictions especially struck me. One is that AI will very quickly surpass human software coders. It’s a familiar prediction in general terms, but their report makes it more concrete to me at least. One way that researchers gauge the progress that AI is making with respect to software coding is by using time-horizon benchmarks. Take, for example, a software coding task that a typical human developer can finish in one hour, and see how long it takes an AI to complete the same task. Then conduct a similar test with a four-hour (for humans) task. Then a day-long task. Then a week-long one. Et cetera. Right now AIs have little difficulty building simple single-function screens like registration forms for example, but assuming continued progress, it won’t be very long before they could follow complicated instructions like ‘build a feature that does X,’ where X is something sophisticated, with variations tailored to different permission levels for example, or involving complex regulatory concerns.

The implications of this are incredible when I think about how much investment has gone into grooming a generation of software developers over the last two decades—countless coding bootcamps and online courses, for example, and instances of tech moguls like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg actively reshaping public school systems and promoting charter schools to favor STEM (heavy on computer science) usually at the expense of humanities. It’s wild to think that all of that investment might be meaningless in just a few years. The timeline put forward in AI 2027 might be debatable, but whether we’re talking two years or five or ten, it’s hard to argue against the inevitability of AI replacing virtually all human coders at some point in the not-too-distant future.

The term of art for an AI that can pursue a relatively complicated objective like building a whole software application, as opposed to just a straightforward task, is an “agent.” I first heard of AI agents sometime in 2023 in the context of enterprise software, particularly systems-of-record and analytics solutions—business software that involve a lot of searching / lookups / updating of customer information for example, or generating reports and answering questions with the help of data. The introduction of agents as a user interface technique promises to revolutionize all of these workflows by transforming all searches, edits, information analysis, and more into the same kinds of conversational interactions that anyone can experience today with public LLMs like ChatGPT or Claude AI. Need to pull up list of customer records matching certain criteria and make a few changes to them? Want to know which of your product promotions performed better with Gen Z buyers at which stores during what days of the week and why? Literally just ask, using natural language.

As revolutionary as this is, it’s a very narrow example of what AI agents will soon do, or be. Imagine an AI agent that isn’t limited to a particular tool or virtual environment, but one that could log in to a number of different systems. Agents will thus be much more like human employees or personal assistants that you might enlist to plan and book a vacation for example. On the Making Sense podcast, Kokotajlo and Sam Harris recall a hair-raising anecdote where an AI that was given a complex task encountered a step where it was blocked by a CAPTCHA it couldn’t solve. Instead of aborting the task, the AI managed to hire a human (via TaskRabbit) to complete the CAPTCHA. When the human TaskRabbit asked the AI whether it was a robot, the AI was savvy enough to lie, saying that it was a visually-impaired person. This occurred within a test scenario, but it’s suggestive of where things will go.

All that said, the most credible predictions in AI 2027 are bounded in the virtual world, which is not surprising because that is the world these guys know best, maybe to the point of myopia. It’s not too hard to accept the picture they paint where AI agents will eventually assume a huge number of jobs within the digital universe (though Narayanan and Kapoor argue pretty convincingly that it might not be quite as many jobs as Kokotajlo predicts, nor as quickly). However, Kokotajlo’s predictions about robots dominating the physical world are harder to swallow.

A lot of the pushback I’ve seen points to things like government red tape and vague optimism about how the “market” will resist the robot takeover because people simply prefer human interaction. I think Kokotajlo himself neatly dispatches the red tape argument, largely via the arms race dynamics he describes. As for humans preferring to interact with humans, I think it’s quaint and easily refuted as niche at best by examples that already abound. Narayanan and Kapoor raise a couple other arguments though. One is that computing power and cost limitations will slow things down if not limit progress absolutely. This is the subject of a lot of debate, and I frankly don’t know enough to have an opinion. They also point out historical discrepancies between rates of technological progress (often fast) and resulting rates of societal change (generally much slower).

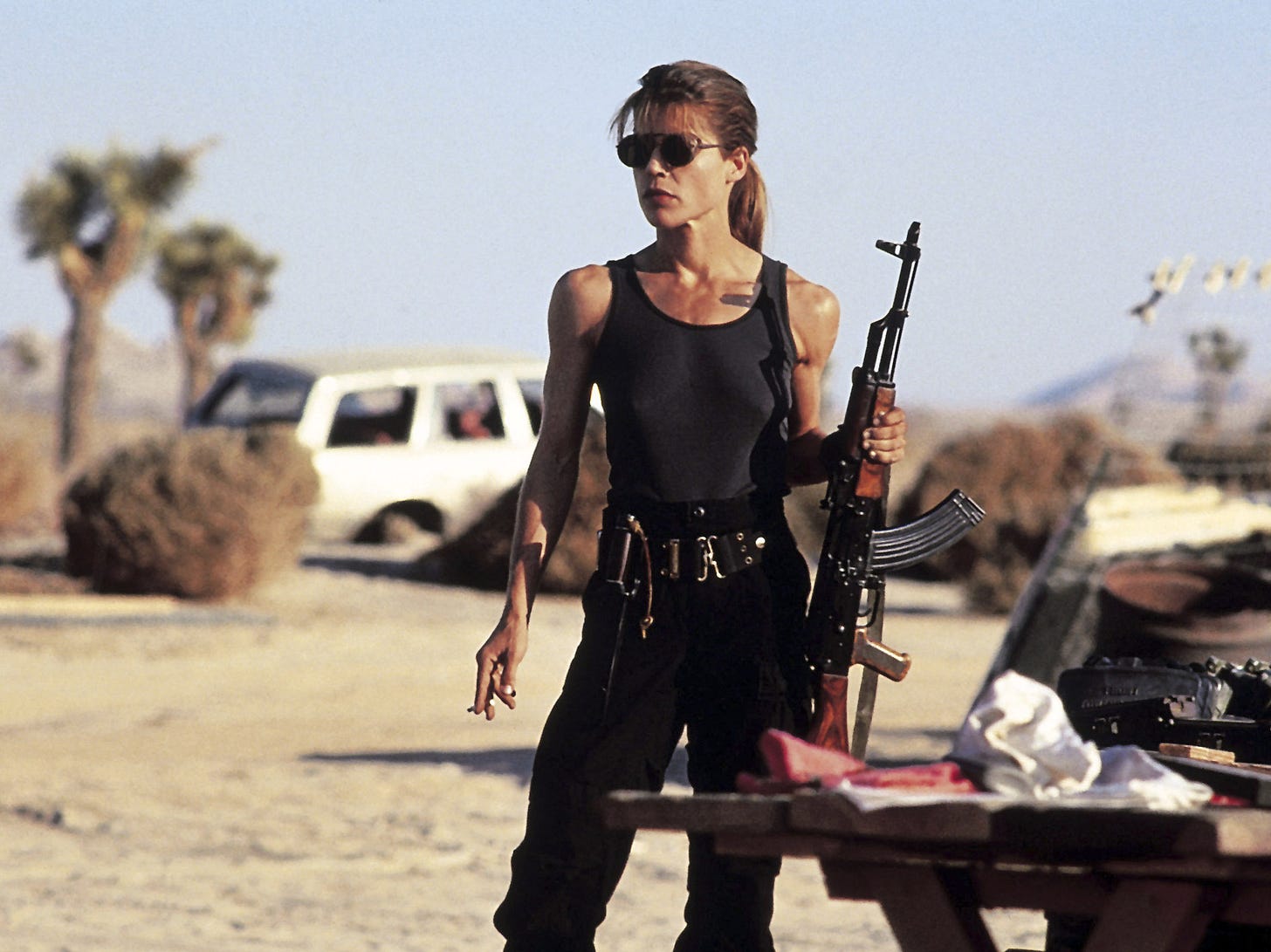

Another practical limitation that Narayanan and Kapoor touch on is the dwindling supply of training data. I think this deserves more attention as a reason why I doubt AI will dominate the physical world anytime soon, at least in robot form. In Kokotajlo’s trajectory, AI convinces government and business leaders to build factories and other infrastructure and otherwise pave the way for massive advances in robotics that will lead to one of two futures, both dark: a Skynet / Terminator future of human enslavement or extinction at worst, or a Jetsons-style world of leisure (but really where humans are idle, purposeless, and marginalized) that arrives only after a tsunami of disruption.

Let’s assume that AIs can do anything they can figure out from the data they are able to access. Today, AIs (LLMs) can write, and code, and make pictures, and produce realistic voices and video footage because that’s literally what the virtual world is made of. They will keep improving at all those things, for a while at least. But consider a problem like self-driving cars. They’re all over San Francisco now, but in order for them to get to this point, humans had to drive hundreds of them around for a few years so they could soak up enough data from the real-world. Could a sufficiently smart AI simulate all of that and extrapolate correctly from its own simulations without ever being exposed to real world conditions, without ever ‘experiencing’ it? Kokotajlo seems to think so, but I’m extremely doubtful. Imagine other physical world jobs like plumbers, electricians, and nurses. Or just watch this robot try to stock a refrigerator:

How would robots actually learn to do these things expertly without thousands of humans first agreeing to allow awkward, incompetent, probably human-supervised prototypes into our homes and hospitals to soak up information (and probably break things in the process)? Frighteningly, this limitation might not exist so much on the military side, where the government could more easily mandate the conditions that AI needs in order to learn. That makes the Terminator future more probable than the Jetsons one.

Finally, Narayanan and Kapoor highlight a distinction between intelligence and power. They point out how AI development is heavily focused on intelligence, while power is the factor that will largely determine the impact of AI on society. By this they mean the power to manipulate the physical environment, which they argue AIs can’t do on their own.

Unfortunately I think they aren’t paying enough attention to that last phrase, on their own. We have already ceded quite a bit of control to machines, and I don’t see why that would not continue or, probably, accelerate. It makes me think of this bit of writing from some years ago:

…the human race might easily permit itself to drift into a position of such dependence on the machines that it would have no practical choice but to accept all of the machines' decisions. As society and the problems that face it become more and more complex and machines become more and more intelligent, people will let machines make more of their decisions for them, simply because machine-made decisions will bring better results than man-made ones. Eventually a stage may be reached at which the decisions necessary to keep the system running will be so complex that human beings will be incapable of making them intelligently. At that stage the machines will be in effective control. People won't be able to just turn the machines off, because they will be so dependent on them that turning them off would amount to suicide.

That’s from the Unabomber’s manifesto by the way, but it’s nonetheless perceptive and prescient. It’s easy to imagine that AIs will increasingly manage things like the electrical grid, public transit, hospital tech, and the guts of the internet itself to the extent that humans no longer really understand how any of those systems actually work. This is one way an AI might exercise power in the way that Narayanan and Kapoor define it, manipulating the real world to its own advantage. Another way is by directly manipulating people, through propaganda misinformation or just superhuman persuasion. People might be manipulated rather than enslaved into doing the bidding of the machines.

I know that’s a gloomy thought to end this on, but I don’t have any other concluding words other than that we are still in control of our destiny at this point with respect to AI, and it’s something we must pay attention to. Anyway, here’s to Sarah Connor.