The New York Times editorial board says we have a free speech problem in America, and they are being roundly mocked on Twitter. This type of appeal for civility and tolerance, and against “cancel culture,” has become a full-on genre, with today’s op-ed following close on the heels of this one, which was also met with ruthless mockery. And of course there was this one from a while back, which generated quite a bit of commentary.

For what it’s worth, I’m not down with the mockery. I have some sympathy for the idea that we need to be generous and forgiving towards people who are wrestling in good faith with controversial ideas. I think this comes partly from my upbringing in a very white, Christian community where there was a lot of unspoken racism and overt homophobia. I was fully indoctrinated, and I’m sure I said a lot of dumb things and asked plenty of dumb questions as I made my journey out, things that would not have gone well for me on Twitter.

It is risky to express certain ideas and difficult to engage in healthy debate, especially under the bright lights of social media. But why and how exactly is this a problem, and what exactly does the Times editorial board and the signatories of this genre seek to protect, or defend? This is where the New York Times op-ed falls apart.

What is free speech?

The Times editorial board attempts to draw a distinction between Constitutionally-protected free speech and the “popular conception” of it:

It is worth noting here the important distinction between what the First Amendment protects — freedom from government restrictions on expression — and the popular conception of free speech — the affirmative right to speak your mind in public, on which the law is silent. The world is witnessing firsthand, in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the strangling of free speech through government censorship and imprisonment. That is not the kind of threat to freedom of expression that Americans face.

The op-ed focuses on supposed threats to the popular conception of free speech, but then seems to intentionally conflate this with the Constitutionally-protected kind:

The full-throated defense of free speech was once a liberal ideal. Many of the legal victories that expanded the realm of permissible speech in the United States came in defense of liberal speakers against the power of the government — a ruling that students couldn’t be forced to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, a ruling protecting the rights of students to demonstrate against the Vietnam War, a ruling allowing the burning of the American flag.

The idea here is that since liberals are such passionate advocates of free speech (the protected kind), then it goes without saying that they would also advocate for the popular-conception kind.

The big problem here is one they acknowledge themselves: there is no affirmative right speak one’s mind in public (“on which the law is silent”). There never has been anything resembling such a right, despite what their poll responses seem to indicate (more on that below). No, what the Times editorial board is talking about is the affirmative right to speak one’s mind in public without consequences, without fear of consequences:

Americans are losing hold of a fundamental right as citizens of a free country: the right to speak their minds and voice their opinions in public without fear of being shamed or shunned.

They acknowledge the law is silent on this, but somehow the Times op-ed still claims it is a “fundamental right” to speak one’s mind without fear of consequences.

Amazingly, it doesn’t seem to occur to the editorial board that the “consequences” they’re talking about – most commonly a backlash from one’s audience and maybe shaming on Twitter – is also just people speaking their minds. In other words, the consequences themselves are protected free speech.

Was it ever different?

It’s not quite stated, but the Times op-ed strongly implies there was once a time when people felt free to state their minds, felt no fear. But this is delusional.

The poll itself arguably skews respondents towards the delusional belief that the landscape for expressing ideas was once much safer, but the fact is that every era has had its marginal ideas – ones that are literally in the margins. New ideas are ever emerging, while other ones are on their way out. Once upon a time it was radical to believe that sexual-orientation is genetic, or that animals have emotions. Now these things are accepted. At the other end of the lifecycle are ideas that are on their way out – like the idea that homosexuality is a lifestyle choice. The culture has a natural resistance to marginal ideas, whether they are on their way in or on their way out. No matter the era, a person expressing belief in a marginal idea is met with resistance, possibly shaming.

The margins are fluid and the boundaries always moving, but it has always been risky to talk about marginal ideas, and so people have always engaged in a certain amount of self-censoring. It’s a natural condition of culture and community that we have to consider our audience before we speak, we have to be aware of context, often layers of it.

Let’s not be naive

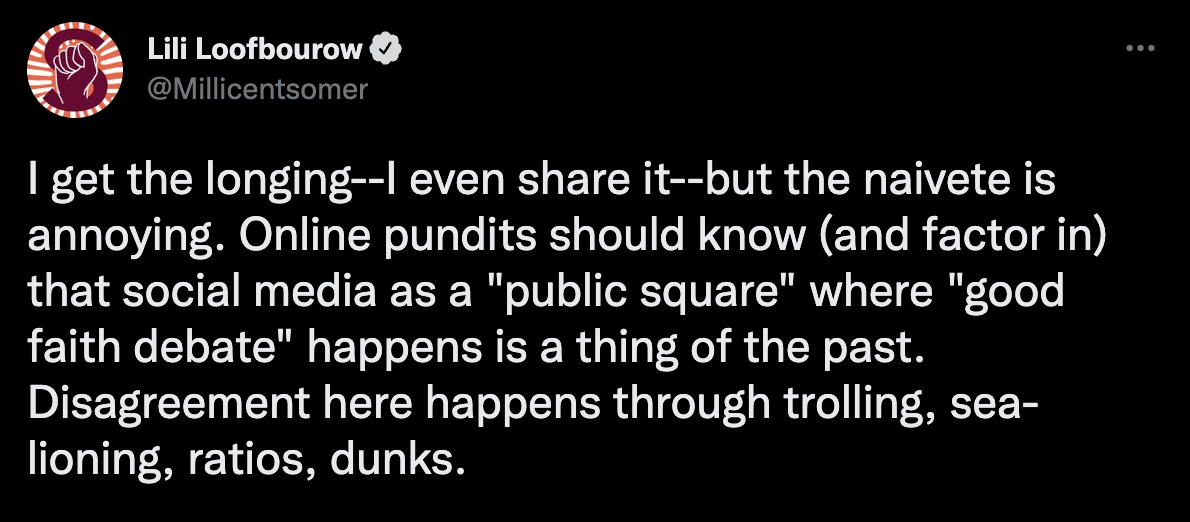

Earlier I said we need to be generous and forgiving towards people who are wrestling in good faith with controversial ideas, but it’s very hard to tell whether someone is wrestling in good faith, and it’s easy to assume bad faith. When Harper’s published their entry into the “free speech problem” genre, almost two years ago, Slate columnist Lili Loofbourow tweeted out a brilliant thread in response. “Bad faith is the condition of the modern internet, and shitposting is the lingua franca of the online world,” she proclaimed. It’s simply naive to assume anymore that most people expressing themselves on the Internet are doing so in good faith or willing to engage in a robust discourse:

In the thread, she illustrates her point with a few tweets about “All Lives Matter:”

Is this sad? Absolutely. Is it fixable at scale? Doubtful.

There is no problem

That there are consequences for saying something stupid, even mistakenly, is not a problem. That people fear these consequences is not a problem. The landscape for expressing ideas is risky, but it’s not as unpredictable as people pretend to think it is.

For the most part, I think people are aware of when they are walking into a minefield. I think it’s safe to assume that a person who has a strongly held belief about a controversial issue – e.g. transgenderism, or Trump, or vaccines – is aware of the potential risk that comes with expressing themselves. They might fear the consequences! If their belief is strongly-held, then it’s also safe to assume that either 1) it is built on a solid foundation of evidence and reason, or 2) the person is not very open to debate or the possibility that they’re wrong.

Once they express themselves, it becomes immediately clear which is the case. If it’s the first one, then navigating the consequences is part of the process; if it’s the second one, then suffering the consequences is part of the game.

Navigating consequences

It’s possible to talk about controversial issues and survive the ensuing pile-on, or even avoid one. This is where the test of good faith happens. Yes, it’s all too rare as Lili Loofbourow says, but it’s not extinct. Good faith requires having some humility about one’s strongly held beliefs – relaxing one’s grip on them so that they’re not so strongly held, or having the patience to gently walk people through one’s arguments. Good faith requires a willingness to admit mistakes and apologize, as well as a talent for apologizing (it’s a skill). Good faith requires awareness of things like character and context.

People who actually operate in good faith rarely suffer the kinds of consequences that the Times editorial board so deeply fears. And when they do suffer consequences, they are able to recover.

I wish I agreed with your take here, since I’ve pretty much agreed with all of the others. But I fear you’re missing the point. It isn’t that botched ideas and conspiracies get wonderfully drowned out by the “marketplace of ideas”. Just imagine a liberal - for the sake of argument, let’s call this person “me” - arguing in public spaces during the summer of 2020, trying to call attention to riots and property damage and “defund the police” as, perhaps, being counterproductive and antithetical to the greater good.

Would I have wanted to voice said opinion anywhere at that time - in my workplace, on social media, in an educational setting? Would my “bad speech” have been corrected by a slew of “good speech”, teaching me a valuable lesson? No, everybody I fucking know would have called me a racist Trumpy mouth-breathing asshole. I, like many good liberals, kept my mouth shut. I’ve been doing the same about several other issues as well; issues that at one point I would have been very comfortable venturing a public opinion on. In my younger life - the 70s, 80s, 90s - there was a far higher respect for the unconventional opinion than there is today; today even a mainstream-ish opinion about trans issues or the state of Israel or whatever is enough to be blackballed. Someone like JK Rowling or Kyrie Irving with money and fame can probably take it; the rest of us pick our public battles very wisely.

THAT was the gist of The NY Times editorial, and it is a position I couldn’t agree with more. Respectfully, the last two lines of your piece, which I keep looking at in disbelief as I type my comment, don’t have a whole lot of grounding in the reality of both the unjustly “cancelled” and the many who keep their yaps closed publicly for fear of personal repercussions.